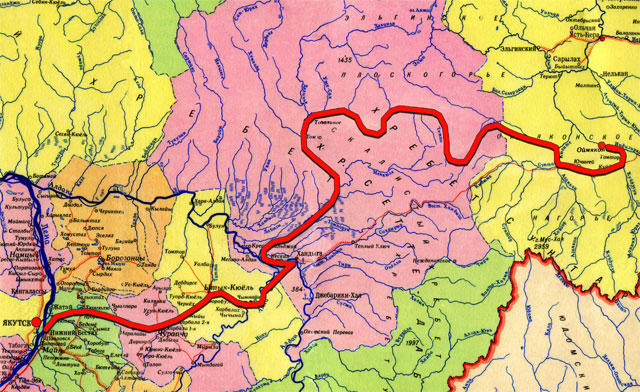

Crossing on sleighs hauled by reindeers 1,300 kms from Yakutzk to Oymiakon, with temperatures around 45-55°C degrees under zero. Oymiakon is the coldest place inhabited by people, with the lowest temperature recorded at -72°C.

I feel paralyzed. Just a moment ago I was contemplating the majestic beauty of the Siberian wilderness and suddenly, without warning, the ice on the Tompo River breaks and our reindeer-drawn sleigh submerges in the chilly waters. The lives of four members of our expeditionary party depend on how fast we manage to get free.

My precarious situation was caused by a condition known as “nalied”, a trap of the local rivers. The phenomenon is typical for north-eastern Siberia, where rivers are usually shallow and freeze down to the river-bed. Subterranean waters slipping through the soil produce enormous pressure that fractures the thick layer of ice with the force of dynamite. The water spreads all over the area, creating a new, thin layer of ice. Such a layer broke under our four sleighs carrying the people and two carrying the load.

Twelve reindeers harnessed to the sleighs and eight loose, auxiliary ones, now desperately try to get out of the water. They fling their legs onto the ice – and the ice immediately breaks under them. Soon frostbite and hypothermia will set in. The remaining four members of our group, safely away from the collapsing ice, rush back to rescue us.

The trapped reindeer are all tied together in a system of harnesses. Walking knee-deep in half-melted slush, we try to free the animals and bring our sleigh to the surface. We have to act quick, as the water is freezing fast. Our “valonki”, cloth boots are now themselves blocks of ice, making it even more difficult for us to move. We are close to collapse, but driven by a superhuman determination. Nobody else is going to rescue us.

First of all we have to free the reindeers off the sleighs. Using our teeth we untie the frozen harness. The animals still fling their legs, but they are getting weaker every minute. They are exhausted, although it is warmer in the water, in temperature close to 0°C, than in the freezing air. After 15 minutes that seem like ages, we manage to free them one by one and help them onto the ice.

Now we have to get the heavy sleighs out of the water. They are stuck under the ice. Our legs are numb and we are thoroughly exhausted. However, we have to bring them onto the ice to be able to continue our trip. They are light and simple, made in a traditional way without using nails. All elements are tied together with leather straps. Breathing heavily, two of us are trying to lift the back of each sleigh up, the rest are pulling it by the harness. After another two minutes we manage to get all sleighs onto the ice.

Andriey, one of the two “kajurs” (local shepherds who take care of our reindeer), makes a fire to warm us all on the riverbank. I remind the members of the group not to come too close to the fire. In a situation like this it is better to warm up gradually. We dig into our luggage for dry socks and another pair of reindeer skin boots. Soon we warm up entirely, drinking hot, sweet tea from huge mugs. However, if it was not for the struggle and physical effort, we would have certainly suffered heavy frostbite. The last thing that we do that evening is break the ice coating off the sleighs.

The silence is so overwhelming that it seems unrelenting and inhuman. The majestic beauty of the white desert. Each morning we get on the sleighs and continue our trek watching the sights moving in front of us, as in a silent movie. Everyone of us has his own way of experiencing the beauty of the dangerous Siberian wilderness.

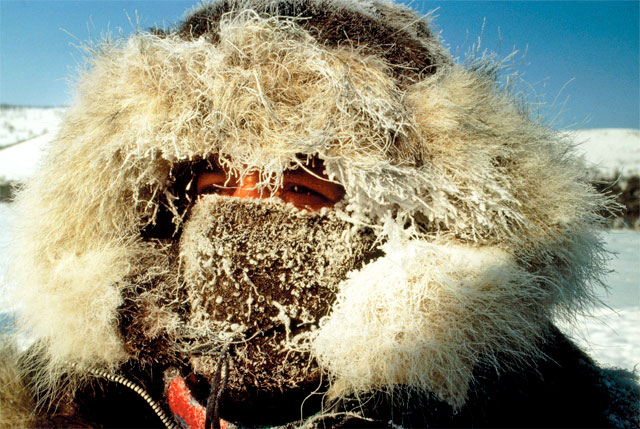

We forget about the cold, but not for long. After a few hours we are frozen. In the temperature reaching 50°C below zero in hour and a half we begin to feel cold. We stop the convoy, jump off the sleighs and run in place to get warm again. In the afternoon we have to do it every hour, then every forty or thirty minutes. The humidity in this region of Siberia is very low, and that helps make the cold less distressing, but any breath of wind fiercely attacks each square millimeter of exposed skin. At 50°C below zero with a strong wind blowing at 40 mph, the chill factor is equivalent to an astounding and windless 100°C below zero.

Suddenly I realize that my hands are totally numb. I pull out the mittens with my teeth and squeeze the bare hands under my clothes, between my thighs. After half an hour I feel an excruciating pain, as if thousands of needles pierced my fingers. I have never experienced such pain before. I would gladly pull my hands out of the warm shelter, but the reason is stronger than the pain. I know that it means that blood is circulating in my hands again and if I want to save them from frostbite, I have to withstand it. I will have to wait till we make next stop.

As hours pass, we make stops more often, totally frozen, our fingers and toes numb. We clap our hands and stamp our feet until the blood returns to our limbs and drink some hot tea from a thermos. The pale sun over us is as cold as ice.

Three days later we are moving again along a border between the taiga and the tundra. Oceans of coniferous trees, mostly larches, pines and firs turn into an icy desert dotted only occasionally with bushes and small trees. There is no single inhabited place in front of us before we reach the Cold Pole. This part of Siberia, called Oymiakon Plain, is known almost to nobody, except for local hunters, who occasionally cross it with their herds of reindeers.

On 34th day of our trip, after cross¬ing the kingdom of snow and ice we reach a road where we detect traces of cars passing. We cannot see them, we just smell the oil and fumes … For us it is the smell of the most expensive cologne – the smell of civilization.

After a large dinner, we go to sleep. We put our fur-lined sleeping bags on the branches now covered with reindeer skins. We change our clothes and soon I can hear the slow, steady breathing of my friends, which means they are all asleep. A few hours later, Markan, a gorgeous reindeer, probably the strongest of our animals, with which we always had a lot of problems as he was very stubborn, falls down on the ground. It dies immediately, as we helplessly stare at it. Andriey explains that reindeers never save energy. They can draw heavy sleigh for hours and hours, without stopping for a moment. During the next two days we loose another two animals, which are so fatigued that they cannot walk.

And indeed, late in the evening we reach Oymiakon on the Upper Indigirka River. This town of 3000 inhabitants during the long winter months is connected with outside world only few times a week, when propeller planes from Yakutsk are landing here. We ride to the center of Oymiakon, where at the foot of the monument witch a plaque: “The Cool Pole.” We all exchange hugs with each other. I can see tears of happiness in the eyes of the men. I examine their faces worn from the struggle and stress, with eyes red from lack of sleep, with long beards covered with ice. We are all happy to have been part of this unique adventure, to have experienced the thrill and satisfaction of reaching the Cool Pole.