In 1986 my expedition successfully crossed Borneo along the line of the equator from Samarinda to Pontianak. On board of canoes and by foot, six men covered 2.500 kms in 31 days of impenetrable forests bringing to end a trip never succeeded by the white man.

I had entered into the largest temple in the world: the jungles of Borneo. Everything was green: the plants, the sky itself, the rivers, the earth. Greens of every shade, breached every now and then by shafts of light from the cloud-filled sky and by the yellow smears of the mud-banks in the river. In the jungle man feels insignificant. There is no comparison between him and the opulence all around.

The smell of rot was overpowering. The trees live as long as their roots can grip in the mud and soft soil of the forest floor. When a tree falls, another quickly takes its place, while the humidity rapidly decomposes the trunk. Termites invade it. Giant ants build their nest there. Larvae, fungus and moss live off it. Before long, it is as if the tree had never existed.

Going to Borneo had been a dream of mine for years. It became a kind of disease; everything I did had this obsession as its final goal. I always knew, however, I would succeed in overcoming all obstacles to organize an expedition through Borneo, from coast to coast, following the line of the Equator for 1500 miles.

The Dayak village was on the margin of civilization in the Mahakam heights at the foot of Mount Muller. Until the river became un-navigable we had travelled in primitive boats powered by an outboard motor. Wherever there are motors progress will be found interfering in traditional ways of life. The animals are taking refuge more and more in the interior of the island while the tribesmen are moving in the opposite direction, to look for modern civilization. Here, “civilization” meant a muddy village of straw-roofed huts on the bank of the river, which is a synonym for life, food and communication.

Human heads were hanging from a charred beam, with their empty eye-sockets playing host to spiders, like grapes dangling from a vine. I looked at them with pretended indifference, but my heart started pounding and the hairs of my neck began prickling like an animal at bay. Were there still headhunters in this jungle?

I looked at the men sitting around a huge caldron of tuac, a somewhat sour drink made from fermented rice. Their faces were impassive. The women were preparing a meal, while tirelessly chewing leaves of sin, a light drug which produces an dopey smile and reddens the teeth and gums.

I was a little ashamed at not feeling any pity for the men whose heads were dangling around me, but for the moment I was too worried about my own safety. I had been assured that headhunting no longer went on, but who knew what might happen so far from the nearest city.

Slowly the tension ebbed away and my companions and I began to relax a little. We had brought gifts, which the natives accepted with dignity: a little medicine, an electric torch, a mul-tri-bladed knife, fishing line and hooks. These common products of civilization are beyond price in the jungle.

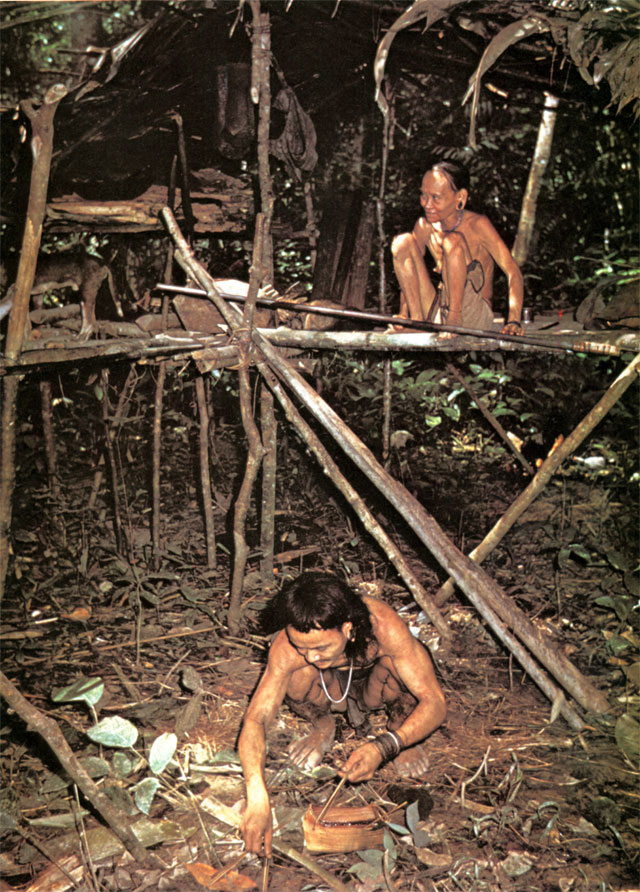

The Dayaks live as they always have done, wrapped in an aura of mystery and cruelty, while in reality, they are a people that has learnt to face the hardship of their life with mildness. There are perhaps 50,000 of them left, protected little and assisted less by the government in Jakarta. Most still insist on living in the long communal houses which are their traditional form of lodging, despite the government’s efforts to persuade them, especially the young, to live in small family units. Living in small houses is fine in the city but in the forest it is more sensible for everyone to stay together.

In the meantime, the last few long houses remain, wooden, thatched, resting on stilts some twelve feet from the ground with a balcony which is used as a stage for rituals and the Dayaks slow, graceful form of dancing. Inside, the long houses are pitch dark except for a flickering fire built on stones which provides a dim light by which one can see the untidy, sad and squalor-filled atmosphere within.

Married women, whose hands are tattooed to indicate their condition, cook the dinner and thresh the rice while holding their smaller children to their breasts. The newly-born, meanwhile, are kept “rolled up” in folds of cloth which are hung from the ceiling in bundles.

Boats are the only form of transport in this place. The Dayaks sail both upstream and downstream by canoe: long, light boats which are kept out of harm’s way by the skill of their paddlers, who live a charmed life in the rock-bound stream of the river. The current is so fast as to make boats almost uncontrollable. Sometimes you are lucky. Sometimes not. We lost part of supplies one day when one of our boats overturned.

The day before we arrived in the village we had pushed our boats by hand upstream for the whole day, struggling to save ourselves and our supplies from the white water and moss-covered boulders of the river, cutting our feet on unseen stones as we waded, soaked to the skin, towards our night-time resting place and the camp fire.

Tiredness was a constant factor. We were sleeping in hammocks, but we didn’t get much rest. We were too conscious of the leeches hanging overhead in the branches, attracted by our smell and by our feet, which were aching from the strain of walking through miles of gripping mud.

The wildlife is extremely abundant. Some species date back to prehistorical times. The monitor lizard, a true monster, still survives here, the last living link with the dinosaurs. It looks like a giant lizard, being more than a meter long, with a crested head and scales whose color merges into the background.

There are also orangutans which the Dayaks call “animal-man” Its last remaining habitats are Borneo and the jungles of West Africa, though forestry is steadily reducing even these. It is now protected by law from the natives, who hunted it ruthlessly, and is no longer to be found near villages or other settlements. On average it lives about forty years. Orangutans are almost human. Mothers bring up their children with endless care and attention and only leave them to fend for themselves when they are more than two years old. They are solitary animals, whose diet of funs, berries and shoots condemns them to roam the forest since all three are in scarce supply.

In my notebook I wrote: “We are travelling at an incredible speed: 100 mph.” 100 meters per hour through an incredible tangle of plant life, which scratched every uncovered inch of our skin.

We were tried and tested to the upmost in every way, but finally we reached the river. We quickly realized, however, that going down river with the stream would be no easier than going upstream had been.

The water seemed calm and slow moving, but when it poured into the narrow opening of a gorge, white water began to appear. Through a thick mist we heard the roar of the rapids, crashing with incredible violence ahead of us. The water writhed, beat against the rocks, frothed, formed swirling whirlpools.

We were stuck in the boat, clinging to its sides with our hands, with a hypnotized stare showing on our faces. The shouts of the helmsman drowned out even the thunder of the water: perhaps he was arguing with nature itself and he was shouting to exorcise its fear. We were utterly drenched, but we were worried most of all for our baggage, films and photographic equipment.

The boat was already full of water and more was pouring over the sides. Our shouts, our conflicting orders, exhortations and swearing all serve to get us over this moment. At one point a wave submerged us all for a second, taking our breath away, while the boat blundered on blindly. We ran into a rock which had been nowhere to be seen before. With an enormous effort I shoved us clear: just a few inches, but enough to set us moving again, albeit temporarily. Our unequal struggle against the rapids seemed endless. Uncomfortably, I looked towards the river’s steep and deserted banks. Naturally there were neither spectators nor rescuers watching us.