Back in Amazonia. Sticky heat, red dirt tracks scratched into the green mantle of the jungle as if by the fingernails of a monster, rivers mudded by the clods of earth they have washed away from their banks, these were all part of my surroundings. For once, however, I was not going to face Amazonia’s hardships on my own.

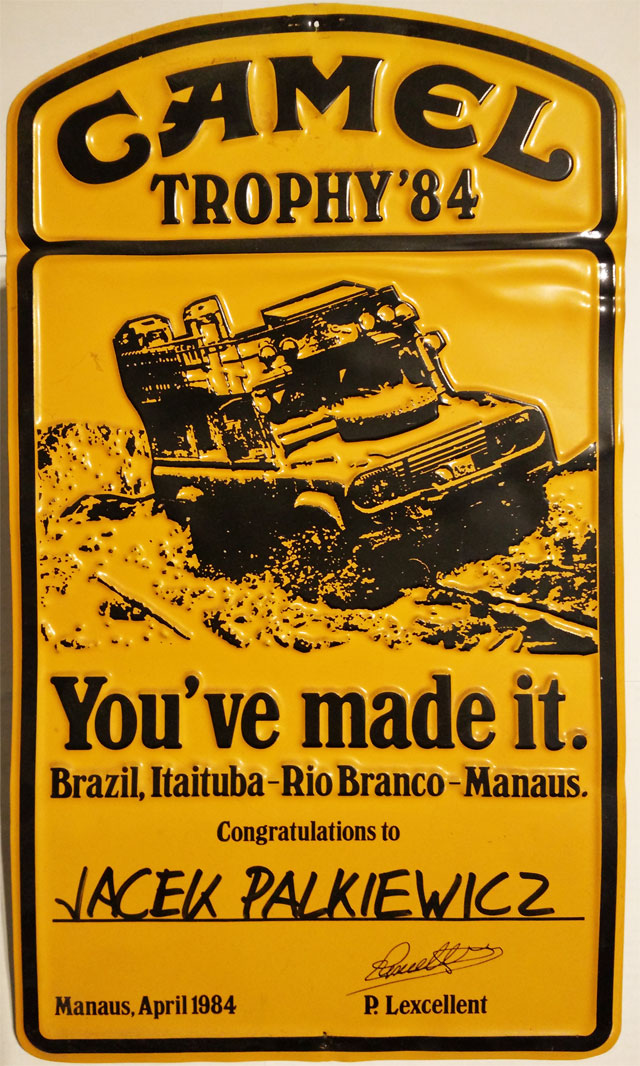

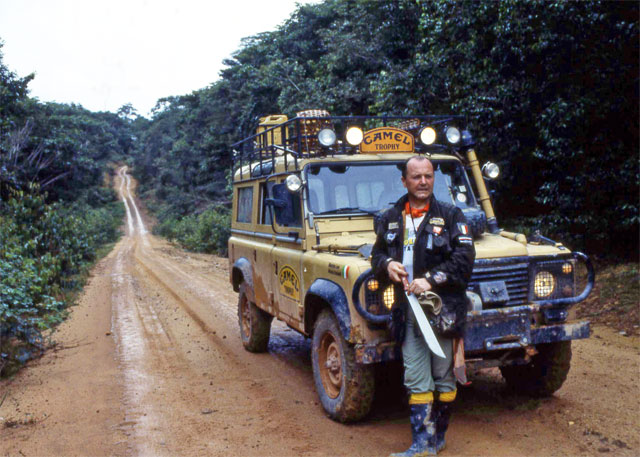

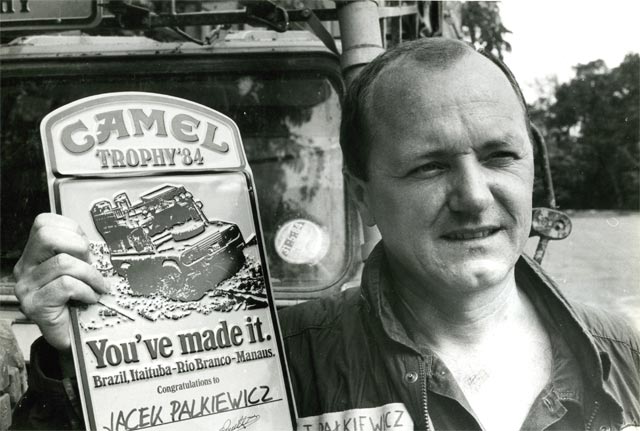

The group I was with was a large one and somewhat diverse in character. A very mixed bag of people, speaking a medley of languages and carrying a vast assortment of baggage, was in the jungle to win the Camel Trophy. Nowadays, the loudest roar you hear in the Amazon are the Land Rovers, which drowns out every other sound.

The official language was English, but from the bivouacs of the various teams voices speaking, all languages could be heard, since many different countries were represented. There were also organizers and journalist, which is why I was there, mechanics and photographers. An authentic caravan of people, living a strange adventure.

There was a keen competitive edge between the teams, since they were representing their countries. This spirit of rivalry, however, was a useful stimulus during the technical trials and the lengthy, difficult transfer stages. In any case, after sunset, when “hostilities” ceased, and the teams met each other around the campfire to talk over the problems of the day, of past adventures and common acquaintances, all rivalry came to an end. Many did not have the strength to talk, however, but fell straight into their hammocks, which were suspended between the jeeps.

The Italian team had a moment of notoriety when it invited everybody to a spaghetti supper, with lots of tomato. They produced a gooey, uneatable sauce which would have been inedible anywhere else but here, for some reasons, it tasted excellent.

Come the morning, the battle was renewed. Land Rovers were revved loudly, bolts were fastened with incredible care, mechanics, their hands filthy with motor grease, replaced engine parts. I wish the men could have been seen at moments such as these, with the streamy sweat exposing streaks of white skin in their dirt-blackened faces until it ran up against the “bandanna” worn by everyone when it was not being used in an emergency as a rag to wipe delicate parts of the motor or as a fly-swatter.

At such moments, the men were entirely different creatures from the “model explorers” who appeared at the press conferences, where they were decked out, as if in uniform, in khaki shorts, clean shirts and polished boots. While actually on the trial, everyone wore what they wanted to and what was practical. Mud splatters and sweat were the only common attire, apart from the mired boots which many would have slipped off had it not been for the danger from thorns, poisonous insects and snakes.

This competition, like many such international events, was taking place during the rainy season and the track through the forest was rendered almost impassable by a layer of thick, wet clay, which was almost impossible to escape. Everybody’s help and effort was required to keep the jeeps moving. One jeep on its own would inevitably have bogged down, but with teamwork progress could be managed. The teams used winches and the super-human willingness of their members to shove stranded vehicles out of the mud inch by inch.

Cries of encouragement spilled out one after the other: “Come on, again, try again, that’s it, we’ve done it, no, hang on, yes, go…” until the first vehicle was through the mud bath, thereafter the passage of the other vehicles became easier because the first jeep could use its power to pull the others through. Useful, too, besides being clear proof that at times a group, working together, can accomplish difficult tasks which a lone individual could never have managed.

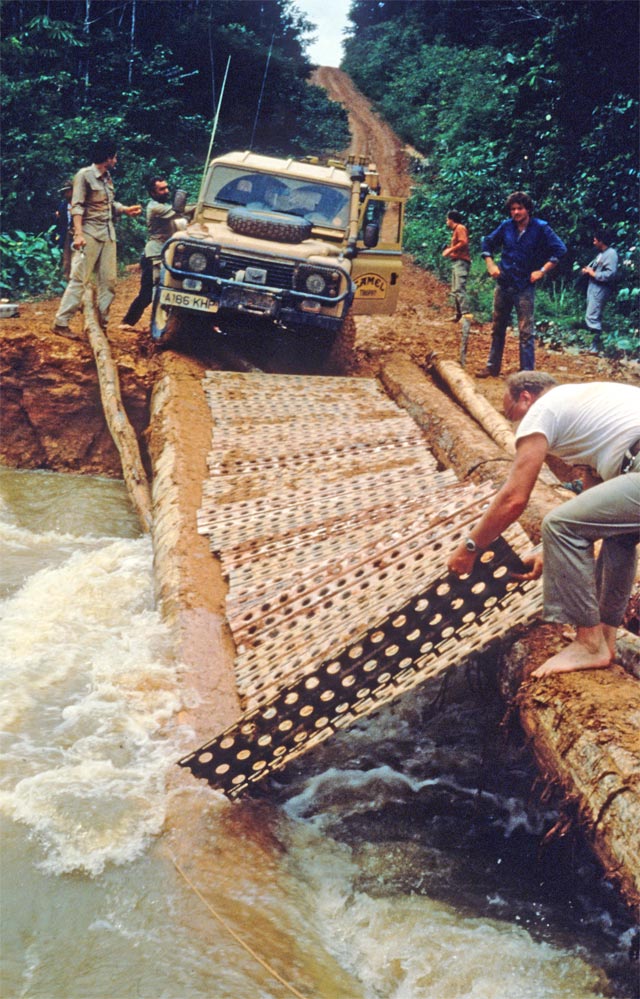

It surprised me to see that there were more things which united us than divided us, despite our different motives for taking part in the competition. When we had to throw a twenty-yard pontoon bridge across a fast-flowing river, a spirit of great cooperation spread among us. Nobody hung back or slacked. There was no other road and if we wanted to cross the river, we all had to chip in, by entering the forest to find trees of the right dimensions, cutting them down, stripping them of their leaves and branches, dragging them to the river bank, all in a sticky heat which seemed to drain your strength away.

The teams were also afraid of being unable to cross. They had no experts on hand to absolve them from the responsibility of failure, though they could use all kinds of equipment. The organizer’s photographers delighted in taking pictures which portrayed them as supermen no obstacle could dismay and the river crossing would provide the best possible opportunity for such photographs.

External observers such as myself also lent a hand, although two Italian journalists, who were already worn out by the trial of the journey, took this latest impasse as an excuse to turn back. The rest of us worked with bowed shoulders all day. By evening, we were disappointed to see that so much labour had produced so little result. We resolved to keep working through the night. The sun came up. Everybody pushed themselves to the limit until we slid the first trunk down on to the river seething with mud.

The banks held and a few men paddled across the river, sitting aside the trunk, carrying ropes to help those who would follow. Little by little the bridge was constructed. The moment of greatest worry, as well as satisfaction, was when the first jeep had to cross. Would it manage? With a great shout of relief, we realized that it would. For safety reasons, we reinforced the bridge before the rest of the expedition passed over. We then gave over a little time to celebrate the completion of a job which would also be useful for the handful of travellers willing to dare this road. A group of garimpeiros, prospectors, had already been waiting a day for us to finish, before continuing their wanderings.

I usually try not to use vehicles on my expeditions, and on several occasions I found myself casting a critical eye over the proceedings, much irritated by the ever-present smell of petrol and by the jeep tracks which rutted the once virgin forest.

“What am I doing here?” I asked myself more than once. I had wanted to try this kind of adventure too, but I found, instead, that I was nostalgic for my solitary expeditions, on foot, through the sounds and smells of the jungle proper, even if… .

Even if I also discovered, aside from my faint irritation with the whole enterprise, which seemed to me to be half-way between an expedition and a circus, that I was curious about the atmosphere of the expedition, which was new to me, and about the men who were taking part. They had been chosen from a dozen countries out of 500,000 applications as the ones best able to conduct this expedition.

The Italians had been chosen several months beforehand, from more than 40,000 applicants. There were a few oddities among them, but on the whole, they seemed like normal young men, dreamers perhaps, but also anchored in the realities of everyday life. Many of them had some experience of travelling in the wild, others had been all over the world, or else were highly skilled mechanics and drivers. What never ceased to amaze me was the serenity and calmness which these boys emanated. They had no need to emulate Rambo to feel fulfilled.

They travelled out of curiosity, or else because they had the taste for adventure. Or maybe they couldn’t bear sitting behind a desk in a jacket and tie. Whatever the reason, they had a path through the mountains or a map printed on their minds, the sound of the wind in their ears, and images of distant places before their eyes. Despite their different walks of life, their common interest in adventure had brought them here.

It was pleasant to meet them, to make friends, exchange news, addresses and stories about “that time in Niger…”. “What?” somebody would reply, “you’ve been there too? I was there a couple of months after you.” “Was that tall chap still sitting outside the bazar?” “Oh, yes… .”

All too soon, we had to stop chattering, set off and plunge through a ford or else affront a difficult section of ground with a white hot-engine that was giving off bursts of boiling steam. All the time our backs were pressed stickly against the seat backs, the insects were tormenting us unbearably, and, while we were dreaming of gulping down a glass of cold beer, we had to make do with a sip of foul-tasting water from our casks.

At other times you can find yourself at a dead end. It had already happened to me once in Borneo when the track simply came to an end in an abundant mass of vegetation. We could have turned round and tried to see if we had mistaken the road, but how were we to know? We went on ahead on foot, to study the ground. The organizers were astounded: “But how has this happened?” They promised us… where on earth does this river come from, it’s not on the maps.” When something like this happens, there’s no point brooding over it. The river might always have been there, or maybe everything had really changed. In the forest, you never know what will happen.

On that occasion, we tried to cut other points, but we were always met by an insurmountable rock wall, as well as by the river. The nearest bridge was some kilometres away. We were doubtful as to what we should do. Our back-up organization had thought of everything, however. They radioed for the helicopter which brought us our supplies of food and beer. The helicopter inspected the area at tree-top level and then returned with good news.

Good? It turned out that after ten kilometres of impassable terrain, the track was again visible. All we had to do was transport our jeeps and equipment over the obstacle. No problem! We empied the jeeps of all extra weight, we packed up our equipment in heaps, tying it up with ropes, strings and anything else that came to hand, and then the jeeps were lifted over the trees by helicopter.

I was left almost alone, looking up, with my hands in my pockets, surrounded by great mounds of stuff. I sat on a tree trunk covered with wet moss and listened, for the first time in the whole journey, to the sounds of the jungle. Whistles, the rustle of leaves, everything which seemed to go quiet whenever we were nearby.

This was the wild I liked. A strong desire to take my rucksack and sneak away came over me. I wanted to be alone here, finding in myself the capacity to overcome every problem.

I had delayed too long. Deadened by the forest, I could hear the sound of chopper blades, coming nearer and nearer. The branches began swaying, the grass started to bend, leaves were blowing. Here it was again, and it would return, for the adventure had to continue…