The boom of the two F-14s shattered the peaceful atmosphere on board the Amerigo Vespucci, where a group of men were quietly chatting about their houses and boats, the wind, and their families. The sunset was casting a glow of eastern mystery over the mosques and minarets of Istanbul, while at the mouth of the Bosporus, a huge American aircraft carrier was cruising majestically.

The contrast between the two vessels was obvious. On the one hand, white sails fanned by the breeze, on the other, nuclear propulsion. The sailing boat also showed the mark of its owner’s care and attention. It was freshly painted black (with two white stripes and gold trimmings which were painted over every year). The aircraft carrier, meanwhile, was gun-metal grey and carried no trace of human intervention on its gleaming exterior.

This notable difference between the two ships might prompt a know-it-all to ask: “What sense is there in having a sailing boat in the navy nowadays?”

On the officer cadet’s training vessel Vespucci, they find this hilarious because without men you cannot sail any kind of ship.

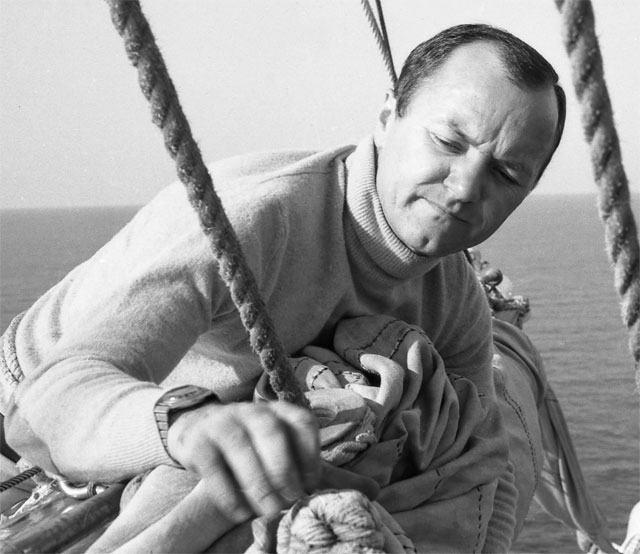

“You must know how to sense the sea’s moods. If you haven’t felt a seabreeze in your face, or struggled to stay upright in a gale, or been showered by spray as you handled the wheel, you aren’t ready to sail a larger boat by computer. On a ship like this, you learn how to react quickly to the unexpected and become well trained enough not to fear the forces of nature,” Dalmazio Sauro explained to me with the enthusiasm of a true sailor.

The Titanic was sailing quietly when it struck an iceberg and sank. The Andrea Doria went to the bottom, despite being equipped with the last word in modern naval technology, after its collision with the Stockholm had left a gaping wound in its side.

Modern instruments have succeeded in eliminating much of the fatigue and many of the risks associated with sailing a large ship. It still remains true, however, that sailing is a man’s job and that one cannot be a good captain if he is not first a skilled sailor.

You learn sailor’s skills by living on board a ship for weeks or months at a time until the boat no longer hides any secrets from you. The wind can drive your boat onto a shoal of rocks, and the waves can fill the hull with water, or flick men from the bridge with ridiculous ease. It has happened often enough in the past. The sea bottom is a unique museum exhibiting galleys, triremes, junks, clippers, oil tankers and aircraft carriers. Often they dragged their crews down with them, no matter how well versed in the art of seamanship they were.

Despite its risks, the sea has always held a special fascination for me. Sailing ships, in particular, has been one of my passions. As Alan Villiers, one of the last men to sail round Cape Horn, once said: “a crossing in a sailing boat is a battle.”

I have walked in square rigged vessels, where boys grow into men, learning discipline and teamwork. Their characters are formed in an indelible manner. From then on, they will remain sailors even if they stay on land for the rest of their lives. I too have known what working long, exhausting days while suffering from cold, sleeplessness, seasickness and fear means. After a while, you loathe the sea and the billowing white pyramid of the sails, which have always held me in thrall. Yet when the storm has died down and a radiant dawn fills the horizon, a new feeling takes precedence. One feels that life is starting anew, and one is filled with pride for having overcome a great test. Until next time, everything is forgotten.

It is tempting to identify yourself with the heroes of Conrad’s incomparable novels. Conrad deliberately neglected the struggles, fear and sacrifices in a sailor’s life and chose to describe only its more romantic aspects.

Life on the Vespucci is not much different from the ships described by Conrad. There are simple wood tables, nails, tow, tar, canvas, masks and rigging. When there is wind, you set sail and go away with God and the rising wind. There are many dangers: shoals, currents, fog, torn sails, broken pumps, the difficulty of laying your hands on the halyard or main brace in the dark, and life boats carried away by the fury of the sea.

Even at night there is no break. Whenever one of the Vespucci’s exhausted students stretches out on their hammock, chilled to the bone and seminauseous from the ship’s pitching and tossing, he never knows whether there will be a whistle from the coxswain to call him on deck. His eyes bleary with lack of sleep, he doesn’t even realize that he is climbing the ratline in the dark. It seems like the height of folly to go up there, but he goes all the same. Once he reaches the yardarm of the mast, he and his mates are caught between two worlds. Above him lighting is flashing and thunder rumbling in the dense clouds, below the sea is hurling great mountains of water to and fro. The wind is playing a thousand different tunes on the taunt ropes of the rigging.

He hears one of his shipmates call out his name: “Corrado, help!” A sail is flapping violently, on a dangerously inclined yardarm, obstructing the cadet’s work. They need to take the sail in hastily or else the canvas, which is stiff as steel metal, will rip itself to shreds.

“Help me reef the sail!”

At that moment, all of Corrado’s life revolves around the reefing point, a coil of cable which must be wrapped round the sail to fasten it to the yardarm. The young cadet forgets everything else as he battles against the canvas. He has got to help his shipmates, despite the precariousness of his position on the narrow gangway, with his chest pressed against the yard. At any moment they might be plucked from the mast and tossed into the sea by the wind, but neither of them pauses to think about this danger. They carry on fighting against the thrashing white mass until their bare hands are running red with blood. It takes strong nerves, strong arms and much courage to reef in that sail.

This is their victory.

But over what? Over the raging sea? Over the hurricane? The forces of nature? No, their victory is far greater. It is a victory over themselves.

The helmsman is also living too dangerously. Killer waves batter against the bridge, sweeping away everything that was not securely fastened down. Salt spray lashes his face like needles. His gorge is rising as the ship rears and bucks among the waves like a horse, and he has to fight to choke back his vomit. Again and again, the waves crash down on him, drenching him with tons of water. He is holding on to the wheel for dear life.

At this moment, someone shouts an order in his ear: “Set a course of 150! Get on with it!” And the cadet does so. The wind is swirling before his eyes, but all he knows is that the compass should be showing 150. Nothing else, the storm, waves, his life or death, counts. 150, get on with it – nothing else counts!

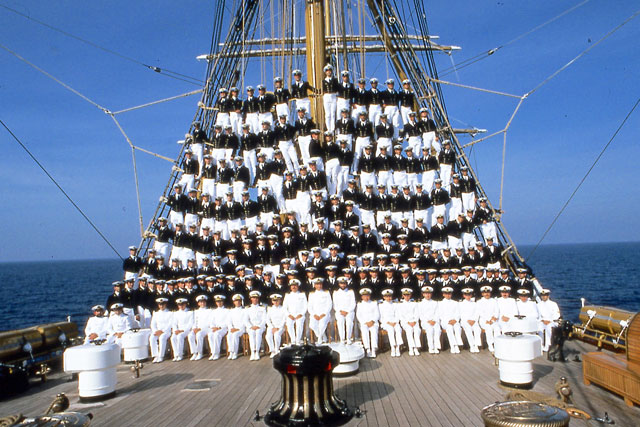

If one considered the value of training ships like the Vespucci from the purely economic and practical point of view, one would swiftly conclude that they were not worth the cost of maintenance. It costs much more to keep the Vespucci at sea than it would to maintain a motored vessel. But it is necessary to keep the human factor in mind. Ten or twelve young cadets are transformed from boys into men, real men, every time the Vespucci sets sail.

All calculations fail at this point. It is impossible to put a price tag on a man.

Computers and high technology are not as important on the Vespucci as force of character, will power and strength. Other values are important too. Team spirit, self sacrifice and, most important of all, love of the sea. Pressed men don’t last long, only volunteers can stand life on board.

What then is the magic which transforms these men, what is the spring which drives them on? You have got to see a sailing boat with its sails fully inflated to understand. One has got to hear the slap of the windfilled sails, to stride the decks, which are scrubbed so often that their cleaners know every plank. You have also got to be a child at heart, able to forget your seasickness – which hits everybody – and to admire the wonders of the ocean such as the dolphins which gambol alongside the ship, the foam at the ship’s prow, the dawn seen through the mist and romantic sunsets. At such moments, your blistered hands, aching back, and salt-reddened eyes are of little relevance. The pride you feel when you go ashore in your dress uniform, with your ship’s famous name embroidered on your cap, also serves to help you forget the rigor of life on board.

I have always had particular sympathy for the man who is any ship’s true heart: the coxswain. You can’t describe a ship without describing him. On the Vespucci, for instance, Mario Garuti’s life and career are inextricably interwoven with that of the ship itself.

The coxswain has always been the favorite character of writers of novels and screenplays. Besides, he constitutes – and has always constituted – a vital link in the chain of command between the crew and the officers. He is the captain’s right arm and sometimes left as well. In all the navies in the world, he is considered as important to the captain as the main-mast itself. On the Vespucci, the coxswain is a particularly important figure, since the captain is replaced every year. The coxswain’s experience and skill are often invaluable to the new chief.

There is also another category of sailors. These are the men who have rounded the legendary Cape Horn under sail. These aristocrats of the sea have three rights which other sailors do not have: the right to spit into the wind, to whistle while on deck and to wear an earring in their left ear. These rights are acquired only after a voyage which has terrorized crews for centuries, claiming an endless roll of victims. Calm seas are rare in those latitudes, which are known as the “Roaring Fifties.” More usually, a crossing must be made against the will of icy winds, which whip up the sea in rage and test the crew’s courage and skill to the limits.

In 1909, the Susanne was delayed in those waters for 99 days, 90 of which were stormy, before it succeeded in rounding the Cape. The Susanne faced every one of those days as if it were her last, yet never succumbed to the terrifying waves. Others were not as fortunate as the Susanne. In 1905 alone, 43 vessels foundered, 15 of them with the loss of all hands.

Heroic sailors often go unrecorded, since, when disaster strikes, there are usually few witnesses. In 1957, a training ship of the German Navy, the Pamir, sank in the Atlantic after its cargo shifted. Only 8 of the 80 youths on board survived. Their deaths caused a bitter public debate in which many doubted the utility of these remaining “floating cathedrals.” Common sense prevailed in the end, however. Training voyages continued, providing young officers with a reservoir of experience which enabled them to foresee the wiles employed by their pitiless opponent, the sea.

Now do you understand, my dear know-it-all, why sailing boats are essential even in a modern navy?