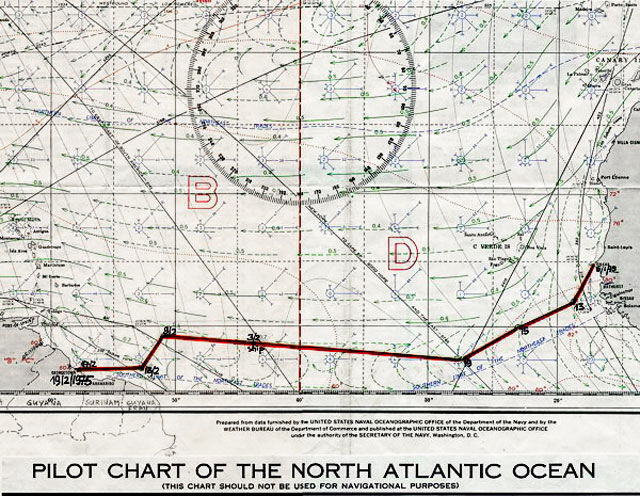

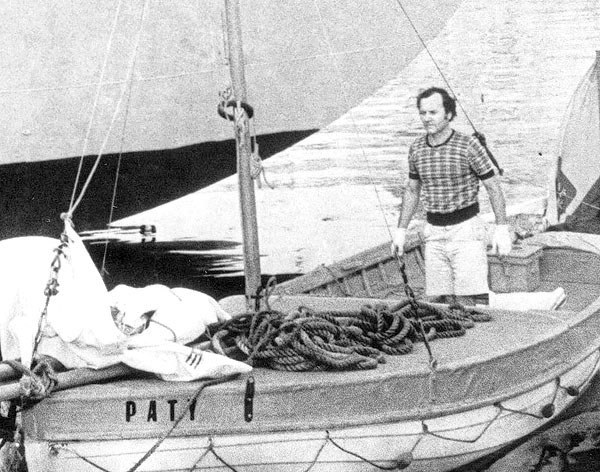

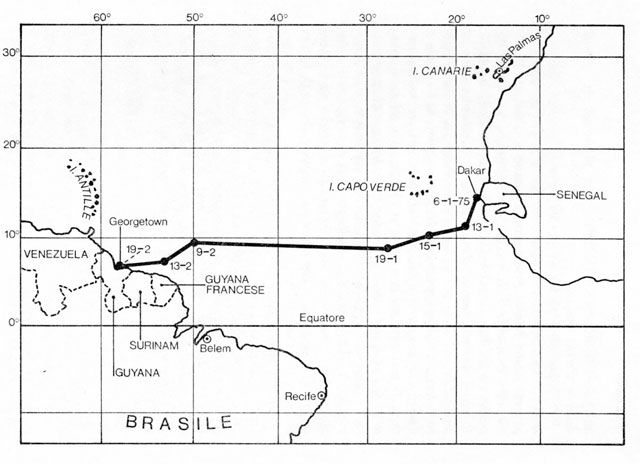

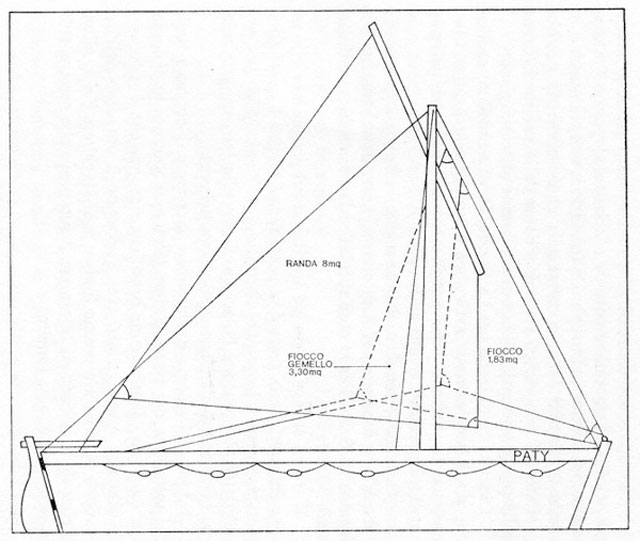

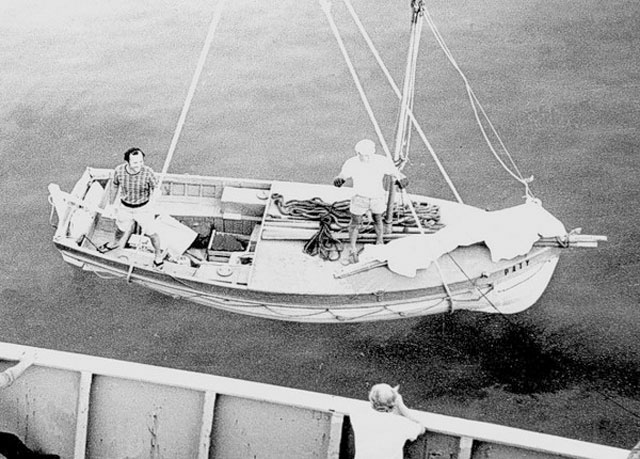

In the autumn of 1974 I have purchased an old lifeboat (5.5m long, 15m2 sail) and in January 1975 without sextant, wind rudder, or radio, departed from Dakar, Senegal, and sailed to Georgetown, Guyana. This was a venture that, given the type of boat, had been attempted by very few solitary navigators in the history of sail. After 44 days of struggle against the fury of the ocean, the sleep, the tiredness, the cold, the damp of the night and the torrid heat of the day, I managed to cross the Atlantic ocean, touching earth in South America.

One day recently, a little daughter of a friend of mine asked me a surprising question: “Is it true”, she inquired, “that you crossed an ocean on your own?”

It was a hot afternoon. We were lying in the shade thrown by some palms, sipping Jamaica rum and mango juice. From time to time I allow myself a moment’s weakness, and for a second there I found it difficult to recall an event which had taken place so long ago, and in such different circumstances.

I stayed silent for a while, before memories from decades before came rushing back and I was once more alone in the middle of the ocean.

Chapped face and hands, parched lips, a singlet stiff with brine. Around me, nothing but water, marvelous and infinite, under a glaring blue sky. Stormy nights, peace and tranquility, the murmurs of the waves, the creak of the rigging, solitude, anxiety, long days and long, endless nights.

“Yes, I really did cross an ocean, though now that the calluses on my hands and the windburn have disappeared, it seems like someone else’s story.”

Slowly, all the old memories came to the surface, recalling moments of terror and the pride I felt at my victory. Not the kind of victory you win in a game or while betting, but a victory over myself, for having reached the goal I had set myself despite all the obstacles in my way.

How I used to admire and envy the men who went off to sea. How I used to dream of the stories in Conrad’s novels, which I read when I was a boy. I used to be able to smell the salt of a tropical sea, feel the heat of white sands and hear the rustling of the palms even when I was living in Poland, where the sea is never turquoise, the sand is always grey and wet and palm trees don’t grow. I couldn’t stay there. The visions aroused by writers who spoke of the sea as if it were a living being were too compelling.

During those six weeks I crossed the Atlantic from Dakar to Georgetown, I was never able to escape either from myself, or from the difficulties which constantly arose. I used to speak and shout to myself, to rejoice and break into tears, to tremble with fear, but in the end I won through, with no one to help me.

I was never free from fatigue, nor from the anguish of loneliness. I who loved the sea so deeply now began to hate it, while secretly fearing that “he” would realize my betrayal and take his revenge. I used to speak to the sea. I had no one else. I spoke out loud to both God and the sun. It seemed then that they were listening to me and that somehow they would answer. Nowadays, people hardly ever speak to each other, and if they do, they rarely listen.

I was missing human company. Like any sailor, I swore during every storm that I would never again set foot in a boat so long as I lived, if I survived to put my feet on solid ground. You never keep this promise, but at the time you believe it and the thought consoles you.

In all my life, I have never come closer to giving up as I did on this occasion. After three days of uninterrupted storms, with the waves tossing me how and where they liked, I had reached the limits of my resistance. I yelled, “That’s it, I surrender” to the sea and decided that I would fire my distress signal as soon as I saw a ship. All I wanted was to be put out of my misery. I couldn’t eat or sleep and I was shaking with fear and cold. I was covered with sores from head to toe because I couldn’t keep a square inch of myself dry. What sense was there in going on suffering?

I was muttering to myself in self-commiseration. I no longer had the strength to struggle on. I was so drained by my battle against the elements that I just wanted someone else to intervene and take matters out of my hands. Only the decision to surrender seemed able to bring me peace of mind.

Two days passed by before I saw a ship on the horizon, and by then the sea had returned calm. The course it was steering was bound to bring it across my own and so I had no need to fire my distress flare. When it approached I saw that all the sailors were busily preparing for my rescue. The ship, which was the Cuban oceanic exploration vessel, the Antarctic Ocean, was a hive of activity. A rope ladder had been lowered down the side of the hull, a lifeboat was being readied, the crew were waving to me, smiling, and shouting encouragement. I seemed to hear them calling, “Your struggle is over, here we are, come on board.”

But my inner voice was far stronger. I had already forgotten the dark days of the storm and my own despair. For a moment I hesitated, but then the weakness passed. Inside me I heard a stern, decisive order: “No! Don’t give up. Don’t take the easy way out. You can do it on your own. Don’t abandon your dreams.”

That “no” I heard as I bobbed beneath the towering sides of the Antarctic Ocean echoes in me every time I feel the temptation to surrender. I am glad, because I have come to know that the determining force in every victory is the belief that you are going to win.