For many years, Venezuela’s authorities have effectively stopped intruders from penetrating the regions largely unexplored to this day along the Venezuelan-Brazilian border inhabited by the last primitive Yanomami. Scientific projects or medical missions are very rarely allowed.

We set off a week ago with Puerto Ayacucho on a twelve meter long carved single trunk bongo with two engines attached to it. After passing the natural Casiquiare channel connecting two large river systems, the Amazon and Orinoco, we entered the off limits region. The Esmerald settlement, in which Alexander von Humboldt, the father of modern scientific geography, stayed in 1880, marks the final lodgment of civilization and practically no one can cross this border.

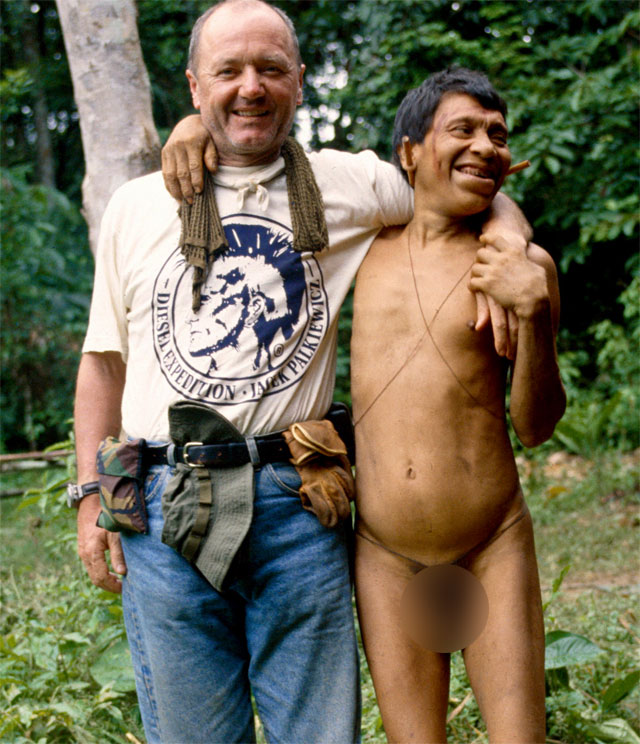

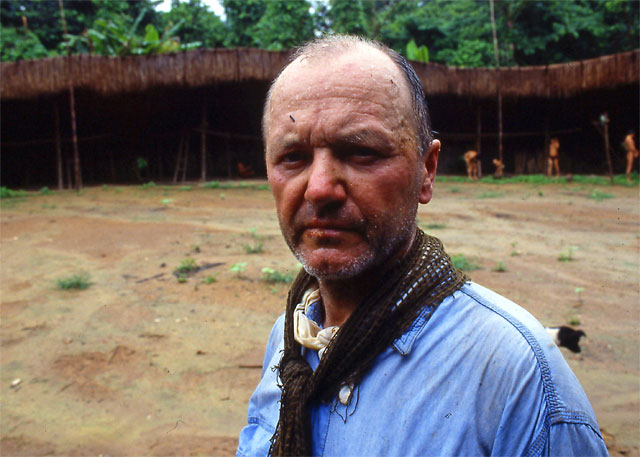

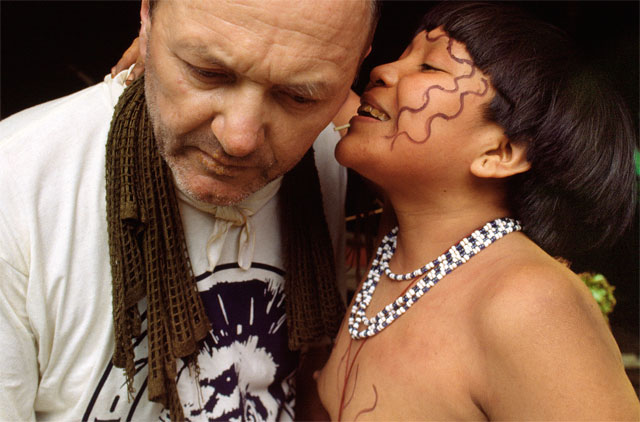

The farther up the river, the more dangerous the bends and rapids become. On the fifth day, we reach the oasis of the primitive world. The children run away screaming to embrace their parents, the Indians gather around, showing their amazement at the intruders. In the blink of an eye, they change their facial expressions from a smile to an alarmed or threatening look. We are received by the chief whose name sounds like Roharve, who greets us but never ceases to swing in his hammock. His raw face does not give away any emotions. We place our gifts into his hands: machetes, pots, fishing lines, and hooks. In order not to get the natives accustomed to receiving presents free of charge, I suggest the chief exchange all our wealth for several bows, arrows, and baskets weaved from plant fibers.

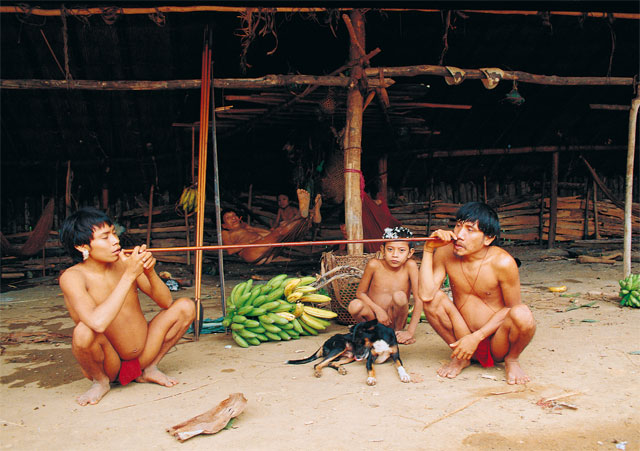

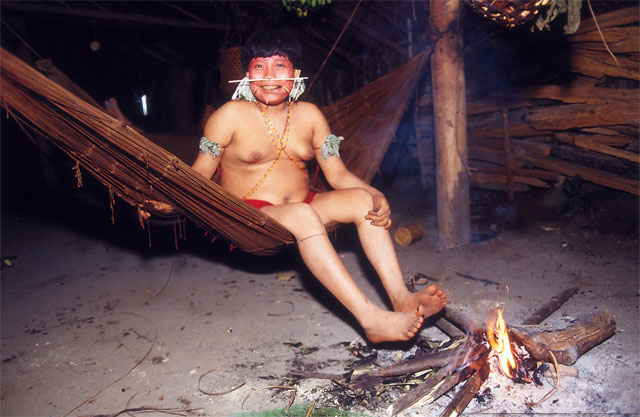

We receive shelter in a shabono, the great common house of the Yanomami, with a characteristic circular shape and diameter of at least 50 meters. There is no outer wall or partitions separating the places inhabited by individual families. Covered with a braid of palm leaves, one giant roof resembles a big canopy. I am struck by the functionality of this design and its perfect adaptation to the needs of social life, guaranteeing a sense of security in the primeval jungle. Dozens of families live here, each focused around their own bonfire. There are baskets, quivers, bundles of tobacco leaves, banana bunches, and various items belonging to individual families on the pillars supporting the roof.

Life in a tropical forest is not idyllic, and every second newborn baby dies here. The equatorial climate is lethal, and the jungle is full of traps. Digestive tract and parasitic infections spread everywhere. Motherhood is a difficult test, women age prematurely, and only a few survive to the period of menopause. Their average life expectancy does not exceed thirty years.

The ever-progressing economic development is synonymous with destruction for the Indians. The territorial expropriation process contributes to this, combined with environmental devastation, the construction of roads, logging forests, the exploitation of oil and the search for gold. Clashing with a world unknown to them up till now and with 21st century technology such as helicopters, TV, weapons, drugs and power shovels has forced the Indians, including their weakest and most vulnerable, to become addicted to foreign habits. The invasion by white man means rape, epidemics, alcoholism, prostitution, illnesses and humiliation.

However, the Yanomami’s assimilation seems inevitable. Our generation will probably be the last to witness their existence. Despite various solidarity campaigns aimed at defending these Indians, their fate is closed. Missionaries say leaving them alone condemns them to death. “If I had to choose between the preservation of Indian cultures and their total assimilation, I would choose with deep sadness the modernization of Indian communities. There are priorities, and the main priority is, of course, the fight against hunger and poverty,” wrote Mario Vargas Llosa.